The 88 temples of the Shikoku pilgrimage offer a unique door into the island’s culture and the Buddhist mind.

Text: Kajsa Skarsgård Photos: Christina Sjögren

“Get in the car.” An old woman in thick glasses and a knitted hat gestures from her seat behind the wheel.

We wouldn’t normally jump into a stranger’s car that has suddenly stopped in our path, and the grandmother in the car probably doesn’t pick up any strangers either, but this is Shikoku and we are wearing the white, pilgrim clothes.

Sumiko Nagamori, 83 years old, knows exactly where we are heading; she has completed the Shikoku pilgrimage four times.

The 88 temples honouring the founder of Shingon Buddhism in Japan, Kōbō Daishi, are scattered along the pilgrimage circuit of 1400 kilometres.

Devoted people, fortunate with an abundance of time and good health, walk the pilgrimage in one go, completing it after about six weeks. Most pilgrims of today, however, take years to complete it, returning when they can and moving forward in the ways that they are able to. ‘There is no right or wrong way’, is an often repeated mantra in the guidebooks about the Shikoku pilgrimage.

Two days before getting our first, but not last, ride from an old lady, we set off on this spiritual journey with a week at hand and a wish to experience different parts of this beautiful island, by foot and local transport.

*

It all starts outside the little train station of Bando in Naruto, where we find a green line painted on the street, leading us through the quiet town towards temple number one of the Shikoku pilgrimage, Ryōzen-ji.

The scent of incense reaches us before we see the temple. Two ferocious statues guard the gate, accompanied by a mannequin in full pilgrim costume: white clothes, a sedge hat with Kōbō Daishi ’s name, and guiding messages, printed on it: a walking stick: a monk’s stole and a mala,the prayer beads.

In the shop at the back of the temple we change into the pilgrim jacket and sedge hat, a transition that also helps to focus the mind on the reformative intentions of the journey.

The monk Kōbō Daishi, who is also known as Kūkai and as an engineer and a calligrapher, lived from 774 to 835, but it was not until the 1600’s that the pilgrimage in his footsteps became popular among the general population.

It is now becoming more common for foreign tourists of different beliefs, together with more secularized Japanese people, to participate in the pilgrimage as a way to contemplate on life in beautiful, spiritual settings. As long as the practicing Buddhists and the culture at the temples are respected, everybody is welcome.

Before entering the main hall we light three incenses, one for the past, one for the present and one for the future. Hexagonal brass lanterns hang close together from the ceiling, creating a sense of a honeycomb casting a warm light over us. In here there are texts we can only appreciate for the beauty of their calligraphy, and statues of deities we are not yet familiar with, but the space speaks a universal language of deeper meaning.

When the temple closes, we don’t walk far down the street before a woman smiles at us saying “O-henro”, the name for the Shikoku pilgrim. Suddenly, we find ourselves sitting by her table with drinks in front of us, and towels in our hands that she has given us as presents. The tradition to give pilgrims gifts is called osettai, and it is seen as a way to participate in the sacred journey.

We are not the first pilgrims who have been welcomed into this woman’s house; she shows us a box full of name slips with the image of Kūkai, the same kind of name slips pilgrims offer at the temples. We leave her ours, and step out into the evening with a great feeling of gratitude.

*

The next day we stand outside the main hall of Konzō-ji (temple 76) where a giant mala hangs. A man in jeans and a plaid shirt has just announced his pilgrim arrival with a resonating dongfrom the old bell.

”Tokyo busy, heart busy,” he says to explain why he has come here, introducing himself as Yoshihiro Sasaki.

He likes the freedom of choice that the Shikoku pilgrimage allows, and he is doing it by car during a week of holidays.

We have come here walking past rice paddies and vegetable fields tucked in next to family houses. Today we want to reach Zentsū-ji (75), but for the pilgrim the way is more important than the goal, and walking through the landscapes of Shikoku’s everyday life is as humbling as the most beautiful temple.

Zentsū-ji proves to be worth a visit also for its own sake. Here you can do a symbolic pilgrimage around the statue of Kūkai surrounded by 88 statues representing the 88 temples. Under the hall where the house of Kūkais birth once stood, you can do an enlightening walk through a 100 metre passage of complete darkness.

The five storey-high pagoda at Zentsū-ji is as impressive as the giant camphor tree close by, where Kūkai himself is said to have enjoyed the shadow on hot days. Along the temple wall, hundreds of statues of arhats stand side by side, all human-size and with a bald head, but each with their own emotional expression, so alive nobody would feel alone in their company.

On the bridge marking the transition back to the outer world, we meet two pilgrims, taking advantage of their day off as a chef and a waitress in a nearby town. Soon we are in their car, invited to a restaurant to eat sanuki udon, the local dish that has put the Kagawa prefecture on the gourmet map of Japan.

Between the slurping sounds of the delicious noodles disappearing into our mouths, we talk about why we are doing the pilgrimage.

“I want to reset, to recharge my energy and clear my mind,” says the chef, Norihisa Kayahara, and we all agree.

*

The following days we head south, towards Cape Ashizuri. We ride the train through luscious mountains and over scenic bridges, hike on ancient forest trails and through villages we would never have known if it hadn’t been for the o-henrosigns leading our way.

The temples we visit all have their particular beauty. The woodwork at Kokubun-ji (29) is enchanting, Chikurin-ji (31) is renowned for its garden, Zenjibu-ji (32) overlook the Pacific Ocean, and at Iwamoto-ji (37) locals have decorated the ceiling with their own paintings, portraying both a cabbage and Marilyn Monroe.

In the cities it is easy to find accommodation, in the more desolate areas local advice can be helpful. The night before we reach the most southern temple, on Cape Ashizuri, we stay in a tatami-room in a guesthouse recently opened by a surfer couple in Tosashimizu-shi.

The beach is only a five minute walk away, and it is possible to hike along the coast to the temple Kongōfuku-ji (38). We take the bus, passing through views of dramatic cliffs dropping into the Pacific Ocean and fishing villages hidden away in the bays.

Kongōfuku-ji lies on a mountainside near the sea, enclosed by dense forest. The sound of trickling water follows us everywhere in this oasis, and around the pond where carps glimmer a garden of stones rise. This is one of the most far-away temples, but it is also one of the most stunning places, and close by are trails through a national park leading to the glistening white light house of the cape.

Before leaving Shikoku we go back north to Kan’onji. The town is famous for its sand sculpture of a huge coin dating back to the 1600’s, which we view from the hill leading up to the neighbouring temples Jinne-in (68) and Kannon-ji (69).

There we find pilgrims chanting sutras, creating a comforting melody that adds to the stillness.

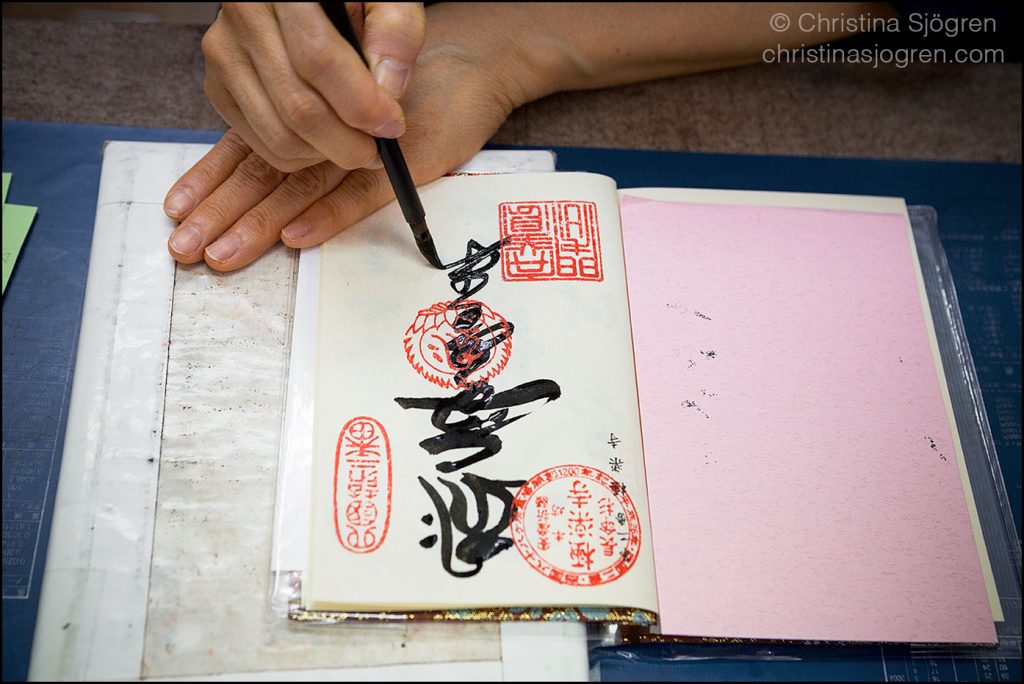

One man is dressed fully in white and the pages of the book in his hand are brightly red. It is the book where the pilgrim collects the temple stamp after worshipping. This man has completed the pilgrimage 78 times.

He gives us a photo of the sun, then we exchange name slips. His are of golden paper, a sign of the many pilgrimages he has done. Ours are simply white; we have not yet even visited all the 88 temples once. We are only at the start of a greater journey, and we will definitely be back.

The article was published in The Japan Times on March 23rd 2018. More photos can be found on Christina Sjögrens website.