Lacking other heirs, the 16th generation Yoshimoto bladesmith passed on the lineage to his Canadian apprentice, Murray Carter, who successfully has created an international interest for his unique knives.

Text: Kajsa Skarsgård Photos: Christina Sjögren

The chef at the sushi restaurant down the road does not know that the 17th-generation Yoshimoto bladesmith works in the neighborhood, yet this craftsman’s knives are used in the White House and worldwide. Murray Carter’s forge can be found in a garage at the end of an anonymous suburban block of small businesses in Portland, Oregon.

From the garage, a door smudged by sooty hands leads to an office and unassuming cutlery shop. Framed children’s paintings hang on the wall alongside Japanese scriptures, one of them an account of Emperor Hirohito’s visit to the Yoshimoto bladesmith shop in Kumamoto in 1931.

“I am the safe keeper of my lineage’s documents and mementos, including a samurai sword my master’s great-grandfather made,” says Carter, a middle-aged man with light eyes and a boyish smile.

A selection of his hand-forged knives are displayed in the glass counter, but almost all sales are done online.

Fortunately for the fate of Carter, his master’s cutlery store in the city of Kumamoto was more striking. It was the sight of the impressive blades in the shop’s window that enticed the 18-year-old Canadian to walk into the shop. There he met Yasuyuki Sakemoto, the 16th-generation Yoshimoto bladesmith.

Carter had come to Kumamoto to study chitō-ryū karate, but he returned to Canada with a new goal. He started studying Japanese at university and convinced his dean to let him do several courses in parallel. After a year he graduated with the equivalent of four years of Japanese language studies.

“I did it because I wanted to go back to Japan,” Carter says. “And because that’s how I do things.”

He went back to Kumamoto and asked, in fluent Japanese, if Master Sakemoto could teach him to forge knives. Carter was welcomed into the forge and over the next six years he divided his time between teaching English and learning to become a traditional Japanese bladesmith.

Rather than being the stereotypical authoritarian teacher, Sakemoto coached Carter and encouraged him to also learn from other blacksmiths around Japan.

“You get burnt, your fingers bleed from grinding so much over stone and you fail. The forge is a very strict and unforgiving teacher,” Carter says. “It was a perfect balance of that, my own high expectations on myself and the compassionate teaching of Master Sakemoto that made this possible.”

Carter had no intention of becoming the next-generation Yoshimoto bladesmith, but after a few years it became clear that neither had anyone else.

When Sakemoto took on the craft from his uncle, he did it because he felt the responsibility to uphold a tradition and a knowledge that would otherwise die away. So when Carter accepted the great honor of becoming the 17th-generation Yoshimoto bladesmith, Sakemoto was relieved.

In between the name of Carter and Yoshimoto are the three moons, stating that the blade is made by a Yoshimoto bladesmith of the house of origin.

Leaving teaching and trying to sustain his family of six as a full-time traditional bladesmith came as a rude awakening for Carter, but he never had second thoughts.

“The fire, the hot steel and the sharp knives — it’s so thrilling,” he says. “The fact that I would always come back to the forge excited to make another batch of knives was a self-sustaining validation that I was in the right profession.”

However, Carter found it difficult to be recognized as the traditional Japanese bladesmith he had become. He wasn’t granted a dentō kōgeihin seal, the official mark recognizing traditional craftsmanship — a decision he believes was based on the fact he is not Japanese. Although he made respectable kitchen cutlery and not the outdoor knives stigmatized as weapons in Japan, he was often referred to as the “gaijin (foreigner)who made naifu,” he says, rather than the hōchō (kitchen knife) bladesmith.

“There’s a subconscious discriminatory edge to it because a naifu (knife) is used to kill people with and it is an English word. It’s foreign, an invasion. It’s what Japanese would call batā-kusai — a Western thing stinking like butter,” says Carter.

After 18 years in Japan, Carter immigrated with his family to the United States, the world economic center for cutlery, where he hoped to reach his full potential as a bladesmith. Starting over in a new country was difficult, and just as his business was picking up pace, the global economic crisis of 2008 slowed everything down. So, it is with pride that Carter says he is now looking to hire a 10th person at Carter Cutlery.

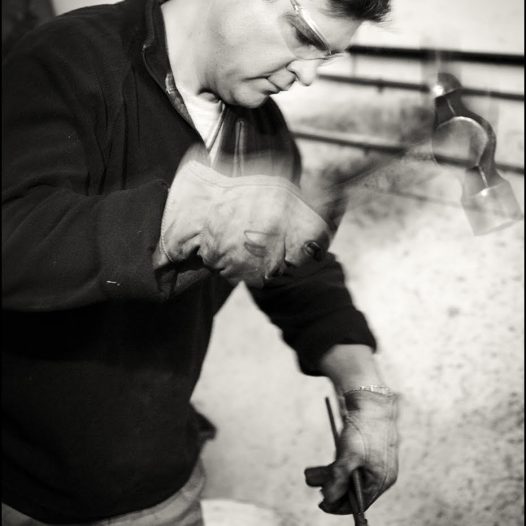

In the garage workshop, two of his paid apprentices are busy assisting him. One is dedicated to the making of the wooden handles, some in traditional Japanese style and others of Carter’s own design. The other is devoted to the grinding and sharpening of the blades, using both traditional water wheels and modern electric belts to get the perfect edge.

Carter spends most of his time in the corner by the small forge. He built it simply with bricks as a temporary solution when he opened his first shop in Japan in 1995. However, it served him so well that it traveled to America with him. On the side of the forge there is a box of coke for heating the steel and a bucket of Japanese rice straw ashes where he lets the blade cool down slowly.

His knives are forged according to the same techniques his bladesmith ancestors used to make katana swords, using high-carbon steel laminated with softer steel to make the blade as strong, thin and sharp as possible.

Carter shuffles the bits of coke into the forge. The fuel source is crucial since the heated steel acts like a sponge. He doesn’t use coal because it emits sulfur, which softens the steel, and gas ovens are oxygen-rich and cause the steel to lose essential carbon.

Small impurities in the coke light up in yellow flames and Carter makes sure they burn off before he puts a piece of white steel in the forge. The steel is beaming hot when he takes it out with a pair of tongs and places it under the beat of the Japanese power hammer, flipping the steel back and forth with rhythmic precision.

The smaller the grain of the steel, the stronger the blade, so Carter repeats the process of forging over and over while simultaneously shaping the steel into a kitchen knife. The enhanced bend in the silhouette of the knife is his own mark; he calls it the “Carter elbow.”

The 23,000 knives he has made have also marked him.

“My hands shake, my eyesight is going and I have muscular problems from working long days standing on concrete for the past 27 years. I am fiercely loyal to the 420 years of lineage and the 16 generations of blacksmiths before me,” says Carter.

Every year Carter travels to Japan, and in October he will bring his apprentices and introduce them to Master Sakemoto. Talking about him, tears suddenly roll down Carter’s face.

“I’m overwhelmed by a tremendous gratitude to have been in his presence so many years,” Carter says. “But being young I didn’t fully realize what a great man he is. I squandered some opportunities and was not always as respectful as I should have. Our relationship is a gift from the universe I never deserved.”

With his own group of apprentices, Carter is now trying to create a business built on collective effort where both authority and profit is shared, believing harmony is the way to success.

So, who will be the 18th-generation Yoshimoto bladesmith? Carter’s own children are not striving for it.

“It’s hard work and it’s only for the most passionate that can’t help sleep, talk and live knives,” Carter explains. “But I’m confident that a person that demonstrates the right aptitude and attitude will appear and that there will be a seamless transition.”

But for now, Carter says, he is content.

“Instead of me wrestling with the knives and exerting my will over the iron, we are more like a duet in a harmonic relationship now. My knives are straighter and harder than ever and more of a joy to use. And Carter Cutlery has shifted from being about me to include these young men who I can help grow into a direction beyond anything I could achieve.”

Looking back on his life, Carter continues:

“Did I achieve what I hoped to when I moved here? Beyond my wildest dreams. But it was harder than I ever imagined and it wasn’t on the path I had thought.”

Published in The Japan Times, May 10, 2017.

More photos of Murray Carter on Christina Sjögren’s website.